The American Loan Landscape: A Data-Driven Analysis

That Warning Light on America's Dashboard Is Real: Deconstructing the Auto Loan Surge

---

Jamie Dimon doesn’t do subtlety. When the CEO of JPMorgan Chase says, “When you see one cockroach, there are probably more,” you don’t dismiss it as idle chatter. You start looking for the nest. His comment, a reaction to the bank’s $170 million charge-off from the bankruptcy of sub-prime auto lender Tricolor, was a clinical, unsentimental warning. And the data suggests he’s right to sound the alarm.

For months, the narrative has been one of a resilient American consumer. But a dispassionate look at one specific sector—the $1.7 trillion auto loan market—paints a far more troubling picture. This isn't about one or two isolated corporate failures like Tricolor or the auto parts supplier First Brands. This is about a systemic pressure test on lower and middle-income households, and the initial results are not encouraging. The numbers are speaking, and they’re not whispering.

The tremors began with the pandemic-era stimulus. I've looked at hundreds of these market dislocations, and this particular pattern is a classic case of a well-intentioned policy creating a delayed, but predictable, distortion. Consumers, flush with cash from stimulus and enhanced unemployment, bought cars at inflated prices. Kevin Armstrong, author of a history on auto repossessions, notes people were paying “outrageous amounts for cars that just weren’t going to hold their value.” Dealers, he said, were “laughing all the way to the bank.”

Now, the bill is coming due. The average monthly car payment has crested $750. In 2023, paying off a new vehicle required 42 weeks of income, a sharp increase from the 33 weeks it took pre-pandemic. This isn't a minor shift; it’s a fundamental change in the affordability equation for a non-negotiable asset. The consequence? A surge in delinquencies and repossessions.

The Signal in the Noise

Let’s be precise about the numbers. Car repossessions climbed to 1.73 million vehicles last year, the highest level recorded since 2009. That’s an increase of about 15%—to be more exact, 16% from the year prior and a staggering 43% from 2022. This isn’t a gentle upward trend; it’s a spike. ‘Finances are getting tighter’: US car repossessions surge as more Americans default on auto loans

More concerning is the delinquency rate. A Fitch Ratings index that tracks sub-prime borrowers who are at least 60 days behind on their auto loans hit 6.5% in January. That’s the highest rate in over three decades. George Badeen, who runs a recovery agency in Detroit, puts it bluntly: “Right now, we’re overwhelmed with work.” His lots, filled with the quiet metal shells of defaulted promises, are a physical manifestation of this statistical crisis.

The standard counterargument is that the sub-prime auto market is a fraction of the mortgage market that brought the world to its knees in 2008. This is factually correct, but it misses the point entirely. As Columbia professor Brett House explains, distress in auto lending is a high-fidelity bellwether for the economy. A car isn’t a luxury. For most Americans, it’s a prerequisite for earning a living. People will miss payments on credit cards, personal loans, and even their student loans before they risk losing their car. When they start failing to make car payments, it’s not a sign of casual financial strain. It’s a signal of acute distress.

This makes the current attempts by lenders to manage the problem all the more telling. We’re seeing a massive wave of loan modifications to push back delinquencies. This is the financial equivalent of putting tape over a leaking pipe. It might slow the drip, but it does nothing to address the pressure building in the system. Armstrong notes the high rate of "recidivism" with these modified loans; borrowers often fall delinquent again. It’s a delay tactic, not a solution. The question isn't if the pipe will burst, but when, and how much water will be on the floor when it does.

A Canary, A Cockroach, or Just a Bad Business Model?

So, is every lender a Tricolor waiting to happen? Not necessarily. Tricolor’s collapse is complicated by allegations of “potentially systemic levels of fraud,” which makes it an outlier. We can’t extrapolate its specific fate across the entire industry. But to dismiss it as a one-off event is to ignore the environment that allowed it to fail so spectacularly. Fraud thrives in frothy, poorly underwritten markets.

The real story isn't just about a few firms that engaged in questionable practices or provided bad credit loans without proper diligence. It's about the broader market conditions. Bill Nash, CEO of CarMax, acknowledged consumer "angst" after his company's sales and profits fell. Lenders who, two years ago, were financing "anybody," are now tightening standards. This is a rational response to rising risk, but it also chokes off credit for the very people who are most dependent on it.

What happens when a family that is already struggling with inflated grocery and housing costs can no longer secure one of the online loans or dealer financing options they need to replace a failing vehicle? How does that impact their ability to get to work, to earn an income, to participate in the economy at all?

The problem isn't just the existing book of shaky car loans. It's the cascading effect of a credit crunch in a sector that is essential for economic mobility. We’re not just watching numbers on a screen; we’re watching the potential for a significant portion of the workforce to be sidelined. The government's potential failure to extend healthcare subsidies would only pour gasoline on this fire, adding another non-discretionary expense to already-shattered household budgets.

The Signal is Unambiguous

Debating whether this is a repeat of the 2008 sub-prime mortgage crisis is an academic distraction. The scale is different, but the signal is the same. The data from the auto loan market is a clear, high-resolution snapshot of deteriorating financial health among a critical mass of American consumers. They are running out of road. Ignoring this warning light because the engine hasn't seized yet is not prudent analysis; it's willful ignorance. The canary is gasping for air, and the cockroaches are starting to scatter. The only question left is how many more are hiding in the walls.

-

Warren Buffett's OXY Stock Play: The Latest Drama, Buffett's Angle, and Why You Shouldn't Believe the Hype

Solet'sgetthisstraight.Occide...

-

The Future of Auto Parts: How to Find Any Part Instantly and What Comes Next

Walkintoany`autoparts`store—a...

-

The Great Up-Leveling: What's Happening Now and How We Step Up

Haveyoueverfeltlikeyou'redri...

-

Applied Digital (APLD) Stock: Analyzing the Surge, Analyst Targets, and Its Real Valuation

AppliedDigital'sParabolicRise:...

-

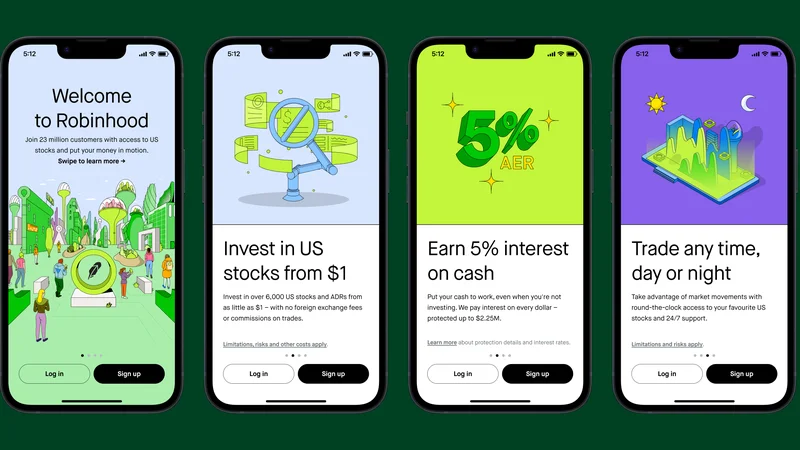

Analyzing Robinhood: What the New Gold Card Means for its 2025 Stock Price

Robinhood's$123BillionBet:IsT...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Fintech 2025: The Breakthroughs Reshaping Financial Innovation, Security, and User Experience

- Google Stock: What They're NOT Telling You About the Price

- Caldera: What Happened?

- IoT: What It Is, Key Components, & The Unvarnished Stock Outlook

- Retirement Age: A Paradigm Shift for Your Future

- Starknet: What it is, its tokenomics, and current valuation

- The Future of Tax: Decoding Your 2025-2026 Tax Brackets and Preparing for Tomorrow's Financial Landscape

- Dairy Queen Chapter 11: Unlocking the 'jackpot' of its next chapter

- Snowflake: The Data Platform, Stock Performance, and AI Strategy

- Cisco Stock: Unlocking Its Next Chapter of Innovation

- Tag list

-

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (30)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (6)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- bitcoin (7)

- Plasma (5)

- Zcash (12)

- Aster (10)

- nbis stock (5)

- iren stock (5)

- crypto (7)

- ZKsync (5)

- irs stimulus checks 2025 (6)

- pi (6)

- hims stock (4)

- kimberly clark (5)

- uae (5)