The Fed's Rate Cut: A Sober Look at the Data Driving the Decision

The Federal Reserve delivered the rate cut the market expected. The problem is what came next.

The headline number was a clean 25-basis-point reduction, moving the federal funds rate to a target range between 3.75% and 4%. On paper, it was a dovish move, the second consecutive cut aimed at shoring up a visibly weakening labor market. Yet, equities sold off. The S&P 500 erased its modest gains. Why? Because anyone listening closely to Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s subsequent press conference understood this wasn't a confident, proactive policy decision. It was a fractured compromise from an institution that is flying blind.

Powell’s message was a masterclass in calculated ambiguity. He stated that another rate cut at the December 10 meeting "isn't a foregone conclusion." In fact, he added, it's "far from it." For a market conditioned to hang on every syllable of Fed guidance, this was the equivalent of a pilot announcing mid-flight that the destination is now "to be determined." Investors weren't reacting to the 25-point cut that just happened; they were reacting to the sudden, jarring uncertainty of what comes next.

The Fed has now cut rates by 50 basis points this fall—to be more exact, 25 in September and another 25 today. Powell noted a clear split on his committee, with some members wanting to "pause here" and others wanting to "go ahead." This isn't just academic debate. It’s a fundamental disagreement about the trajectory of the U.S. economy, and it’s happening at the worst possible time.

A Committee at War With Itself

The most telling data point from Wednesday’s meeting wasn't the rate decision itself, but the vote count: 10-2. This wasn't a consensus; it was a negotiated settlement between two increasingly entrenched factions. On one side, you have Fed Governor Stephen Miran, who dissented in favor of a more aggressive 50-basis-point cut. He sees the flashing red lights of a deteriorating labor market—evidenced by the recent ADP report showing a private-sector payroll contraction of 32,000—and believes the Fed is already behind the curve.

On the other side, you have Kansas City Fed President Jeffry Schmid, who voted for no change at all. His focus is undoubtedly on the still-sticky inflation rate, which at 3% remains a full percentage point above the Fed’s target. He represents the hawkish view that cutting rates further risks reigniting the very price pressures the Fed spent the last few years fighting to contain.

This places Jerome Powell in an almost impossible position. He is not steering a unified ship; he is refereeing a tug-of-war. The committee is being pulled in opposite directions by its dual mandate to maintain both low unemployment and price stability. It’s a classic central banking dilemma, but one made infinitely more complex by the current environment. Powell’s cautious language wasn't a signal of strength or patience. It was a public admission of internal paralysis. How can the Fed project confidence to the markets when it can't even build a consensus in its own boardroom? What happens when the next data print forces the issue and this fragile compromise shatters completely?

The entire situation is a perfect analogy for a complex system under stress. Think of it as an engineering problem. The Fed is trying to land a massive, delicate aircraft (the U.S. economy) on a very narrow runway. Miran, the dove, is worried the plane is losing altitude too quickly and wants to hit the thrusters. Schmid, the hawk, is worried they're coming in too hot and wants to pull back on the throttle. Powell, in the captain's chair, is trying to split the difference, resulting in a policy that might be too little, too late for the labor market, yet too much, too soon for the inflation fight.

Piloting in a Data Fog

Compounding this internal division is an external, and frankly staggering, operational handicap: a near-total blackout of official government economic data. Due to an ongoing government shutdown, the very instruments the Fed relies on to navigate—the Bureau of Labor Statistics jobs report, the Consumer Price Index—are offline. Powell himself provided the only metaphor necessary: "What do you do when you are driving in the fog? You slow down."

This is a remarkably candid, and unsettling, admission. The Federal Open Market Committee is making decisions that will influence trillions of dollars in assets and the livelihoods of millions of Americans based on third-party reports and anecdotal evidence. They're looking at layoff announcements from large companies and private payroll data (like the ADP report), which are useful but are no substitute for the comprehensive, official statistics that normally guide monetary policy.

I've analyzed institutional decision-making under uncertainty for years, and this is the part I find genuinely alarming. A central bank's primary tool, beyond the rates themselves, is credible forward guidance. Powell's press conference effectively declared that guidance is offline pending better visibility. The market reacted accordingly, with the S&P 500 slipping 0.2% (a modest drop, but the reversal from gains was the key indicator of sentiment change).

The crucial question now becomes a methodological one. How does the Fed make its December decision if the shutdown continues and the data fog doesn't lift? Do they rely on a patchwork of incomplete information, risking a major policy error? Or do they pause, as Powell hinted, risking an accusation of inaction if the labor market truly is cratering? Neither option is good. This lack of reliable inputs makes the Fed’s output—its policy decisions and its guidance—inherently less reliable.

The Signal Has Degraded

Ultimately, the 25-basis-point cut is a secondary detail. The real story is the degradation of the Federal Reserve's core product: credible information. The signal is now full of noise, both internal and external. The market is no longer just pricing in economic risk; it's now forced to price in the risk of the Fed itself being divided, disoriented, and data-deprived, a reality reflected in headlines like Powell forced to stave off uprisings in markets and on his own Fed board as his term ends. When the pilots admit they can't see the runway, it’s only logical for the passengers to get nervous.

-

Warren Buffett's OXY Stock Play: The Latest Drama, Buffett's Angle, and Why You Shouldn't Believe the Hype

Solet'sgetthisstraight.Occide...

-

The Future of Auto Parts: How to Find Any Part Instantly and What Comes Next

Walkintoany`autoparts`store—a...

-

The Great Up-Leveling: What's Happening Now and How We Step Up

Haveyoueverfeltlikeyou'redri...

-

Applied Digital (APLD) Stock: Analyzing the Surge, Analyst Targets, and Its Real Valuation

AppliedDigital'sParabolicRise:...

-

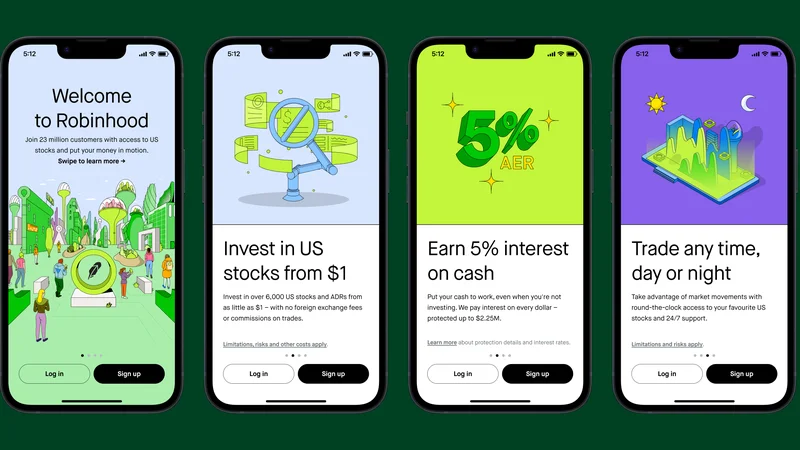

Analyzing Robinhood: What the New Gold Card Means for its 2025 Stock Price

Robinhood's$123BillionBet:IsT...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Fintech 2025: The Breakthroughs Reshaping Financial Innovation, Security, and User Experience

- Google Stock: What They're NOT Telling You About the Price

- Caldera: What Happened?

- IoT: What It Is, Key Components, & The Unvarnished Stock Outlook

- Retirement Age: A Paradigm Shift for Your Future

- Starknet: What it is, its tokenomics, and current valuation

- The Future of Tax: Decoding Your 2025-2026 Tax Brackets and Preparing for Tomorrow's Financial Landscape

- Dairy Queen Chapter 11: Unlocking the 'jackpot' of its next chapter

- Snowflake: The Data Platform, Stock Performance, and AI Strategy

- Cisco Stock: Unlocking Its Next Chapter of Innovation

- Tag list

-

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (30)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (6)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- bitcoin (7)

- Plasma (5)

- Zcash (12)

- Aster (10)

- nbis stock (5)

- iren stock (5)

- crypto (7)

- ZKsync (5)

- irs stimulus checks 2025 (6)

- pi (6)

- hims stock (4)

- kimberly clark (5)

- uae (5)