Enzymes: A No-BS Guide to What They Are and What They Do

These Enzymes Don't Care About Sugar, and Frankly, Neither Should You

Let's be real. Every week, another jargon-stuffed scientific paper drops, promising to unravel one of nature's "deep mysteries." Most of it is academic back-patting, a quiet race for tenure and grant money that has zero impact on your actual life. So when a study about something called "endo-1,3-fucanases" from the "GH168 enzyme family" (Structure-function relationship of the GH168 fucanase reveals an unusual enzyme recognition mechanism for sulfated polysaccharide) landed on my screen, my eyes glazed over so fast I almost got whiplash. It sounds like a droid model from a bargain-bin sci-fi movie.

But I forced myself to read it, because that’s my job. And buried under the alphabet soup is a story so bizarre, so counterintuitive, it’s actually kind of interesting. The story is about a group of molecular machines—enzymes—that are supposed to chew up a tough, slimy sugar from seaweed called sulfated fucan. You might have even eaten this stuff; the wellness industry loves to grind it up and sell it back to you in "functional foods," promising it’ll cure everything from bad moods to bad stock picks.

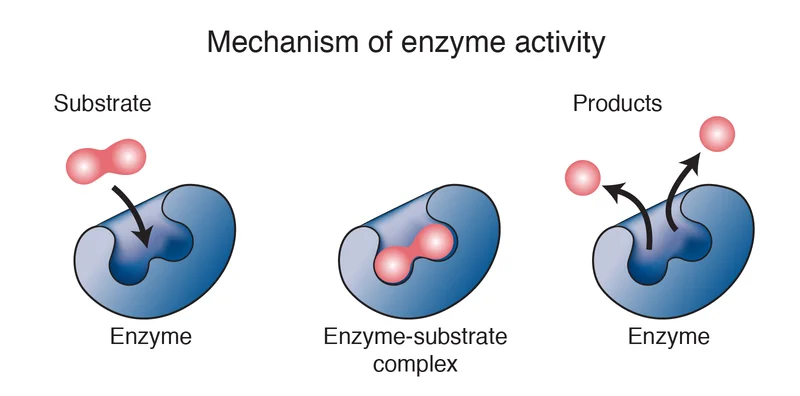

For years, the textbook story of `what is a enzyme` has been simple: an `enzyme` is a `protein` with a perfectly shaped `active site` that fits its target `substrate` like a lock and key. The `enzyme structure` is everything. But these GH168 `enzymes`? They apparently threw the textbook in the garbage. They don't give a damn about the sugar itself.

A Bouncer Who Only Checks Your Shoes

Here’s the twist that makes this whole thing worth talking about. These `enzymes are` supposed to break down a sugar chain. You’d think they’d be experts at recognizing, you know, sugar. But they’re not. Instead, they’re obsessed with the flashy accessories hanging off the sugar: little sulfate groups.

This new research shows that over two-thirds of the enzyme's contact points—the parts that actually grab onto the molecule—are dedicated solely to latching onto these sulfate decorations. The sugar backbone is almost an afterthought. This is like a nightclub bouncer who decides who gets in not by looking at their ID or their face, but by meticulously inspecting the brand of shoelaces they’re wearing. It’s a bafflingly inefficient way to do business, and yet, it works.

The researchers found this family of enzymes has four different "subfamilies," each with its own weirdly specific taste. Some like their sugar with one sulfate group, others prefer two, and one oddball group (Subfamily IV) actually prefers its sugar plain, without any sulfates at all. It's a whole microcosm of molecular picky eaters living in the ocean. And why does this `enzyme function` this way? The paper is full of charts and diagrams, but the fundamental "why" remains a bit of a shrug. Is this just some bizarre evolutionary dead end, or is there a genius to this madness we can't see yet?

And then there's the really wild part. One group of these enzymes, Subfamily II, has a secret weapon. When it finds the right sulfated sugar, a long loop on its surface dramatically swings outward—we're talking a shift of 27.7 angstroms, which is an eternity in the molecular world—to reveal a "hidden pocket." This isn't just a subtle adjustment; this `protein` completely changes its shape. It’s a molecular switchblade, popping open only when it detects the secret handshake of the correct sulfate pattern. It’s a bad design. No, ‘bad’ doesn’t cover it—it’s an insanely complicated and theatrical solution to a simple problem. And I have to admit, I kind of respect the sheer audacity of it.

Then again, maybe I'm the crazy one here. Nature is full of these Rube Goldberg machines that somehow get the job done. Offcourse, we humans think we’re so clever with our engineered solutions, but maybe we’re just playing checkers while marine bacteria are playing 5D chess with `glucose` and `dna` and whatever else is floating around down there. But the practical application of this...

It's Just More Fodder for the Grinder

So, we’ve learned that a specific family of marine bacterial `enzymes` has a peculiar way of digesting a specific seaweed slime. The scientists behind this are undoubtedly brilliant. They mapped the structures, they identified the key "polar knuckle" that makes the whole thing work, and they proved their point with RNA sequencing. Bravo.

But let's pull back from the microscope for a second. What does this actually change? The paper concludes by highlighting its importance for understanding the marine carbon cycle and potentially helping us "utilize" this recalcitrant biomass. Translation: some biotech company is going to read this, figure out a way to use these enzymes to more efficiently break down seaweed, and sell the resulting goop as a new, improved superfood powder for twice the price.

This isn't a breakthrough that will lead to a cure for cancer or cheap, clean energy. This is a discovery that provides a more detailed instruction manual for grinding up algae. It’s fascinating, sure, in the way a documentary about deep-sea fish is fascinating. You watch it, you say "huh, neat," and then you go back to worrying about your rent. The work is elegant, the mechanism is bizarre, but the ultimate impact feels disappointingly small. We’ve just found a sharper knife for a very, very specific kind of fruit that most of us will never even eat.

-

Warren Buffett's OXY Stock Play: The Latest Drama, Buffett's Angle, and Why You Shouldn't Believe the Hype

Solet'sgetthisstraight.Occide...

-

The Future of Auto Parts: How to Find Any Part Instantly and What Comes Next

Walkintoany`autoparts`store—a...

-

The Great Up-Leveling: What's Happening Now and How We Step Up

Haveyoueverfeltlikeyou'redri...

-

Applied Digital (APLD) Stock: Analyzing the Surge, Analyst Targets, and Its Real Valuation

AppliedDigital'sParabolicRise:...

-

Analyzing Robinhood: What the New Gold Card Means for its 2025 Stock Price

Robinhood's$123BillionBet:IsT...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Fintech 2025: The Breakthroughs Reshaping Financial Innovation, Security, and User Experience

- Google Stock: What They're NOT Telling You About the Price

- Caldera: What Happened?

- IoT: What It Is, Key Components, & The Unvarnished Stock Outlook

- Retirement Age: A Paradigm Shift for Your Future

- Starknet: What it is, its tokenomics, and current valuation

- The Future of Tax: Decoding Your 2025-2026 Tax Brackets and Preparing for Tomorrow's Financial Landscape

- Dairy Queen Chapter 11: Unlocking the 'jackpot' of its next chapter

- Snowflake: The Data Platform, Stock Performance, and AI Strategy

- Cisco Stock: Unlocking Its Next Chapter of Innovation

- Tag list

-

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (30)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (6)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- bitcoin (7)

- Plasma (5)

- Zcash (12)

- Aster (10)

- nbis stock (5)

- iren stock (5)

- crypto (7)

- ZKsync (5)

- irs stimulus checks 2025 (6)

- pi (6)

- hims stock (4)

- kimberly clark (5)

- uae (5)