Lake Placid's Changing Shoulder Season: A Data-Driven Look at the 'New' Normal

On Saturday, October 18th, a small concert took place at the Recovery Lounge in Upper Jay, a hamlet in the Adirondacks. The air, crisp with late autumn, was filled with the sound of country-folk harmonies from a Nashville-based duo, "Raising Daughters," and solo artist Robby Hecht. For those in attendance, it was an intimate performance, close enough to hear the scrape of a finger on a guitar string and to speak with the musicians after the last chord faded. One attendee, Julie Robards, described the vocal blend as "breathtaking."

This event is a single data point. And in isolation, it’s unremarkable: a pleasant evening of music in a small town. But when placed against the dominant economic narrative of the region, it becomes a fascinating outlier.

The official story, promoted by regional authorities, is that the Adirondack "shoulder season"—that quiet, economically fallow period between the summer rush and the winter ski season—has been functionally eliminated. The catalyst for this shift was the 1980 Winter Olympics, an event that triggered decades of state investment in tourism infrastructure. The result, we are told, is a robust, year-round calendar of events. This narrative is detailed in local commentary such as ON THE SCENE: Shoulder season has changed in the Adirondacks - Lake Placid News.

On the surface, the data seems to support this. A quick scan of the schedule for late 2025 reveals a flurry of activity: opera at the Lake Placid Center for the Arts, a film festival, a Hall of Fame induction, even a production of a Jean Genet play. It’s a portfolio of events designed to project cultural vibrancy and, more importantly, consistent visitor spending.

But the concert in Upper Jay doesn't quite fit this model. It feels like a different species of event altogether. And that’s where the analysis gets interesting.

The Discrepancy in the Data

If we were to map the region's cultural economy, the official calendar of events would look like a collection of blue-chip stocks. The opera, the film festival—these are institutional, lower-risk assets designed to attract a predictable audience. They are the S&P 500 of the Adirondack cultural portfolio. The concert at the Recovery Lounge, however, is something else entirely. It’s a venture capital seed investment. It’s small, unproven on a large scale (it was only the second time these specific artists had performed together), and its return on investment isn't measured in ticket sales reports but in the qualitative experience of a "breathtaking" harmony.

This is the core discrepancy. The narrative of a "shrunken shoulder season" relies on the aggregation of all activity, big and small, into a single, convenient metric. But lumping a state-supported opera series in with an independent folk show is an analytical error. It’s like measuring the health of a forest by counting both the ancient redwoods and the new saplings as "one tree." The scale and underlying mechanics are fundamentally different.

The official events are top-down, designed to draw consumers to the region. The Raising Daughters concert feels more like a bottom-up expression of a community, even if the artists themselves are imported. And this is the part of the report that I find genuinely puzzling: the official narrative completely ignores this distinction. It presents a flattened picture of success, a calendar packed with logos and dates, without ever questioning the sustainability or authenticity of the underlying assets.

Does a full calendar truly signal a healthy, self-sustaining cultural ecosystem? Or is it a carefully curated facade, propped up by external funding and imported talent, that masks a more fragile local reality?

Tracing the Network Effect

To understand the concert at the Recovery Lounge, you can't look at a regional tourism brochure. You have to trace the network. The performers, Josette Axne and Hallie Riddick of Raising Daughters, are not products of the Adirondack scene. Their story is a map of the modern American artist's pilgrimage. Axne from Colorado and Riddick from Kentucky, they met in 2019 at a theater institute in Connecticut. They moved to New York City, then released their first EP in 2024. Their migration to Nashville happened just six months before this concert.

Their path to Upper Jay wasn’t paved by a state grant; it was opened by a personal connection. Robby Hecht, a veteran singer-songwriter who has been based in Nashville for about two decades—more accurately, 20 years—met the duo at a conference and encouraged their move to the city. Hecht is a node in the Nashville network, a frequent performer at the legendary Bluebird Cafe, and his presence on the bill with Raising Daughters lends them credibility.

This isn't an isolated Adirondack event; it's the temporary landing of a national musical network in a small, rural town. The artists’ journey from Connecticut to NYC to Nashville (a city with a notoriously high signal-to-noise ratio for aspiring musicians) demonstrates a reliance on established creative hubs. They weren't discovered in Keene Valley; they were imported for a night.

This raises a crucial, and perhaps uncomfortable, question about the region's long-term cultural strategy. Is the goal to cultivate and export local talent, or is it to become a permanent importer of talent from elsewhere? One model builds sustainable cultural capital. The other creates a dependency, turning local venues into mere consumption points on a national touring circuit. The current data, as represented by this one concert, suggests the latter. We see the performance, but we don't see the local infrastructure that could produce the next Raising Daughters. The data on that is conspicuously absent.

The Illusion of Aggregation

The story of the "shrunken shoulder season" is a marketing triumph but an analytical failure. It's a classic case of aggregation illusion: by bundling a handful of large, institutionally-backed events with small, independent happenings, you can create the impression of a uniformly robust economy. It’s a convenient narrative that serves tourism boards well.

But the real story, the one told by the quiet concert in Upper Jay, is far more complex and precarious. It reveals a cultural ecosystem operating in the shadow of the giants, one that relies not on state funding but on fragile, personal networks that stretch all the way to Nashville.

This single concert isn't proof that the shoulder season is thriving. On the contrary, it’s a signal that the most authentic cultural experiences are happening in spite of the dominant economic model, not because of it. It’s a quiet outlier that tells us more about the real state of grassroots art than any glossy events calendar ever could. The official data measures the volume; it completely misses the signal.

-

Warren Buffett's OXY Stock Play: The Latest Drama, Buffett's Angle, and Why You Shouldn't Believe the Hype

Solet'sgetthisstraight.Occide...

-

The Future of Auto Parts: How to Find Any Part Instantly and What Comes Next

Walkintoany`autoparts`store—a...

-

The Great Up-Leveling: What's Happening Now and How We Step Up

Haveyoueverfeltlikeyou'redri...

-

Applied Digital (APLD) Stock: Analyzing the Surge, Analyst Targets, and Its Real Valuation

AppliedDigital'sParabolicRise:...

-

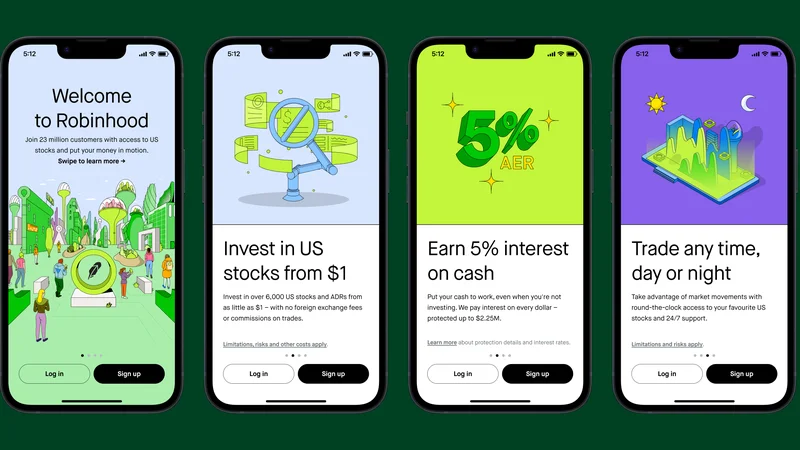

Analyzing Robinhood: What the New Gold Card Means for its 2025 Stock Price

Robinhood's$123BillionBet:IsT...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Fintech 2025: The Breakthroughs Reshaping Financial Innovation, Security, and User Experience

- Google Stock: What They're NOT Telling You About the Price

- Caldera: What Happened?

- IoT: What It Is, Key Components, & The Unvarnished Stock Outlook

- Retirement Age: A Paradigm Shift for Your Future

- Starknet: What it is, its tokenomics, and current valuation

- The Future of Tax: Decoding Your 2025-2026 Tax Brackets and Preparing for Tomorrow's Financial Landscape

- Dairy Queen Chapter 11: Unlocking the 'jackpot' of its next chapter

- Snowflake: The Data Platform, Stock Performance, and AI Strategy

- Cisco Stock: Unlocking Its Next Chapter of Innovation

- Tag list

-

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (30)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (6)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- bitcoin (7)

- Plasma (5)

- Zcash (12)

- Aster (10)

- nbis stock (5)

- iren stock (5)

- crypto (7)

- ZKsync (5)

- irs stimulus checks 2025 (6)

- pi (6)

- hims stock (4)

- kimberly clark (5)

- uae (5)